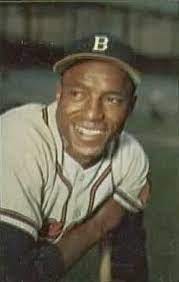

TOT - Braves Trade for Sam Jethroe

The former Dodgers farmhand would become the Braves' first Black ballplayer.

Transaction of Today...October 4, 1949: The Brooklyn Dodgers trade Sam Jethroe and Bob Addis to the Boston Braves for Al Epperly, Dee Phillips and Don Thompson.

Two years after Jackie Robinson wowed onlookers as a Montreal Royal, former Negro League star, Sam Jethroe, joined the Royals. Over a year-and-a-half north of the border, he was impossible to stop on the basepaths. Jethroe looked like he might become the next Black player to join the Brooklyn Dodgers, who also added Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe to their roster to join Robinson. But Jethroe was blocked in the majors - not to mention already in his 30’s - so the Dodgers decided to use him in a trade. And that's how the Braves' franchise was integrated.

Before that, Jethroe briefly made his Negro League debut in 1938 with one game. After a couple of years of semipro ball as he took care of his ailing mother, he would return to the Negro Leagues in earnest in 1942 following her passing. Playing for the Cleveland Buckeyes, the Jet would hit .314/.369/.485 over seven years, playing often in the East-West All-Star Game.

Known also as “The Jet,” Jethroe was one of three players - Robinson included - who were given a tryout at Fenway Park by the Red Sox in 1945. The team's hand was forced more than they were interested in being pioneers because a city counsellor had threatened to pull their license to play games on Sundays if they weren't, at least, open to desegregating their team. In addition to Marvin Williams, Jethroe and Robinson tried out for the Red Sox on April 16, 1945. But despite impressing Red Sox coaches, nothing came of the tryout. The Red Sox would be the final team to field an African American player in 1959.

Instead of joining the Red Sox or even their Triple-A team in Louisville, Jethroe returned to the Cleveland Buckeyes. The Dodgers would later consider Jethroe as they looked to desegregate their team. But Branch Rickey passed on Jethroe at the time, opting for the college-educated and clean-cut Robinson. Nevertheless, Rickey would not forget about Jethroe, purchasing his contract from Cleveland in July of 1948, a year-and-a-half after Robinson made his historic debut for the Dodgers.

With the Royals, Jethroe did everything he could do to get to the majors, hitting .322 in 1948 and .326 the following year. He swiped an amazing 89 bags in '49, including a streak of eleven games with at least one stolen base. That would be an International League Record until future Brave, Otis Nixon, broke it in 1983. But as the season came to a close, Jethroe was still another year older and without a game in the major leagues. The top three outfielders in Brooklyn were all younger than Jethroe, including Duke Snider, who just finished his first full season as the Dodgers' center fielder.

There are two stories about what happens next. The first is that, on September 30, 1949, Branch Rickey sold Jethroe to the Boston Braves for $125,000, the equivalent of $1,464,296.22 today. The other story is that the Dodgers and Braves agreed to a trade on this day in 1949. Going to the Braves were Jethroe and minor league outfielder Bob Addis while the Dodgers received pitcher Al Epperly, third baseman Dee Phillips, and outfielder Don Thompson. The players did change organizations so I'm inclined to believe either there were two separate transactions or one big one involving the hefty bag of money heading to Brooklyn.

Whatever the case, none of the three players the Dodgers got would play much for them. Phillips never even played for Brooklyn while Epperly appeared in just five games in 1950. Thompson did play in 210 games as a reserve from 1951-54, but wasn't much more than a fifth outfielder.

Before we get back to Jethroe, Addis made his major league debut in 1950 with Boston and hit .276 as a reserve the following year. He was dealt to the Cubs nearly two years after the Braves moved him for shortstop Jack Cusick. Later, Addis would be involved in a June 1953 trade with the Pirates that included nine other players and $150,000. Most notably, aging Pirates great Ralph Kiner went to the Cubs.

But Jethroe was the star of the deal. Boston immediately brought him to the majors to open 1950, becoming the first Black player to play for a Boston team along with being the twelfth Black professional ballplayer overall. Considered possibly the fastest player in baseball, Jethroe swiped 35 steals to lead the NL while hitting .273/.338/.442. He showed he wasn't just a speedster, hitting 18 homers along the way. He finished the year with 100 runs scored and ran away with the Rookie of the Year vote, becoming the first Brave to win the award.

His follow-up season in 1951 was even better. He repeated his feat as NL steals leader with 35 more and was only caught five times. Jethroe's triple-slash got slightly higher as he hit .280/.356/.460. He became the 14th Brave and just the sixth since 1900 to reach double digits in doubles, triples, and homers.

Not that it was all good for Jethroe, who had plenty of speed but some defensive issues in center field. His arm was poor and he seemed prone to struggle to pick up flyballs. But he worked hard to better himself and never lost the support of the fans in Boston, who loved to watch him run and perform.

However, things fell off in his third season. Already 35, Jethroe's numbers all went south, hitting just .232/.318/.357 over 151 games. This followed intestinal surgery earlier in 1952. The Braves also changed managers during the season and Jethroe and Charlie Grimm did not get along.

The 1952 season would be the Braves' final season in Boston before moving to Milwaukee. Jethroe was demoted as the Braves opted for Andy Pafko, recently acquired from the Dodgers, and rookie Bill Bruton. The latter, like Jethroe, was known for his blazing speed. The expectation was that Jethroe would head to the minors for only a short time, but instead, he played the entire '53 season in Toledo. He rebounded with a .994 OPS, but couldn't get a shot with Milwaukee.

Following the season, the Braves packaged Jethroe in a trade that included five other players along with cash for Pirates' second baseman, Danny O'Connell. The New Jersey native finished third in the vote when Jethroe won the Rookie of the Year in 1950. After two years of military service, he returned to the Pirates in 1953 like he never left, hitting .294/.361/.401. The Braves thought they found their second-baseman for a decade to join their young offensive nucleus of Bruton, Joe Adcock, Del Crandall, Johnny Logan, Eddie Mathews, and rookie Henry Aaron. But O'Connell would never deliver on that promise.

Meanwhile, Jethroe got only a brief look in Pittsburgh, playing two games and grounding out in his last major league at-bat and the only one as a Pirate. He returned to the minors over the next six years, but never received another shot in the majors. With his career over, Jethroe settled in Erie, PA with his wife and the pair opened up a steakhouse. While the place did well for a number of years, when things went the other way, they went the other way hard. With his debts adding up, he sold his Rookie of the Year award before sadly losing his house to a fire. After the latter, the Boston Braves Historical Association raised money to help with his expenses - just another sign of how much his brief home of Boston appreciated him.

Jethroe's impact on baseball would take another turn. When a friend of Jethroe's former teammate, Don Newcombe, attorney John Puttock, found out about the struggles Jethroe was having, a lawsuit was filed that argued that because of racial discrimination at the time, Jethroe was not given the opportunity that white players had to serve the full four years of service time required during that era to qualify for a pension. The basic premise of the argument was that had baseball been desegregated earlier, Jethroe wouldn't have had to wait until his 30's to get to the majors and would have played the needed four years and should get paid a pension.

Unfortunately, baseball fought back. To be fair, they had the legal standing to do so. The statue of limitations to bring the case, they argued, no longer applied and a judge agreed. But decency won out as a number of owners, spearheaded by Jerry Reinsdorf, agreed to create a special fund for former Negro League players who did not qualify for a pension, providing $7,500-to-$10,000 in annual payments.

A few years later, Jethroe suffered a heart attack and passed away in 2001.

In the end, Jethroe's legacy is not too dissimilar from many of the amazing ballplayers of his era who happened to be born with Black skin and not white skin. We will never know how good of a career Jethroe could have had. What we do know for sure is that Jethroe left an indomitable impact on the game of baseball, the Braves' franchise, and those that were lucky enough to get to know him.

—

For further reading, see this wonderful biographical article by Bill Nowlin at SABR.org. In addition, Josh Jackson wrote this piece in 2011 at MILB.com.