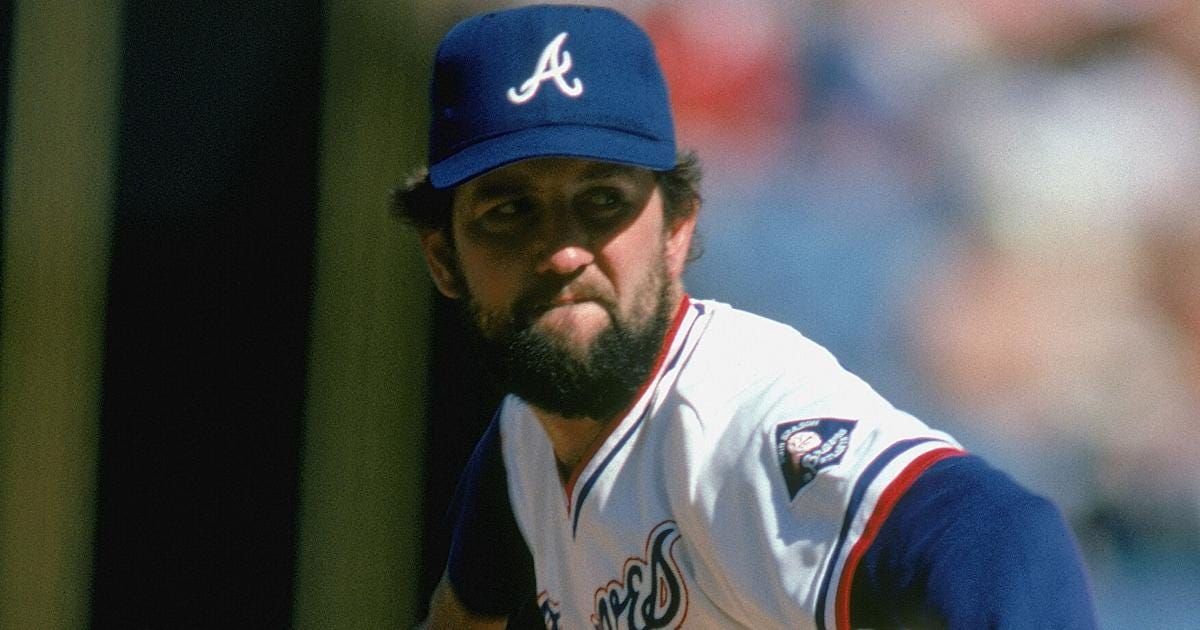

TOT - The Braves Let Bruce Sutter Go

Even though Atlanta released Sutter, they would still pay him well into the new century

(TOT, which stands for Transaction of Today, is a historical look at some of the biggest and lesser-known trades, signings, and other transactions by the Braves franchise on this particular day. More TOTs are linked at the bottom of this article.)

Transaction of Today…November 15, 1989 - The Atlanta Braves release Bruce Sutter.

When Trevor Hoffman was rightfully enshrined in the Hall of Fame in 2018, he joined a sub-group of just two players. Of the 1,035 games Hoffman appeared in, he started the same amount of major league games I, and probably you, started. Zero. He became the second pitcher in history to join Cooperstown's Elite despite never starting a game in the majors. The first guy to complete that random fact? Bruce Sutter.

What the changeup was to Hoffman, the split-fingered pitch was to Sutter. Nasty and downright unhittable at times, Sutter became just the third pitcher to reach 300 saves and the third pitcher to win the Cy Young award despite never starting a game. That's why the Braves gave him a monster contract to come to Atlanta. That decision, like so many other choices during the 80's, would not work out for Ted Turner.

Originally drafted in the 21st round by the Washington Senators in 1970, Sutter opted to attend Old Dominion University. As a James Madison University alum, I'll let it pass because he quickly dropped out and played semi-pro baseball instead. A year after not signing with Washington, he inked a free-agent deal with the Cubs.

Sutter was way ahead of his time. He appeared 116 times in the minors and started just two games. Most relievers of that era - and for a few decades after - only became relievers after being failed starters. Sutter was exclusively a reliever who mastered the split-finger fastball, making him absolutely lethal in short doses. After less than four seasons on the farm, he was brought up to the Cubs in May of 1976.

Sutter spent a year mostly in middle relief but took over as the closer in 1977. For five consecutive years, he was named an All-Star and led the NL in saves for the first time in 1979. He was putting up the kind of dominant stats that current relievers aim for. Nearly 11 K/9 and 1.9 BB/9 in 1977. A 1.89 FIP in 1979. Twice, Sutter finished the year with a Top-10 finish in the MVP race along with winning the 1979 Cy Young.

Many hitters were virgins to the split-finger and their inexperience showed. He was a Cubs fan favorite and a weapon few teams could match.

That made him expensive. After his ridiculous 1979 season, which also included a league-leading 37 saves and a 2.22 ERA, Sutter went to arbitration. The Cubs offered $350,000, which Sutter’s representation argued was too low for the reigning Cy Young winner. The arbitrator agreed, awarding Sutter double what the Cubs wanted to pay him. That was a bump in pay of $475,000. In the NL, only seven players made more money. Of those seven, only Nolan Ryan and Phil Niekro were pitchers. Sutter had a higher salary than 30-year-old Mike Schmidt and his salary was more than double what Johnny Bench, then 32, was.

The Cubs decided that, while Sutter was dominant, paying that much money for about 100 innings of work every year was a bit too much. After the season, they traded him for three players to the Cardinals.

With St. Louis, Sutter continued his dominance. He led the Senior Circuit in saves three times, including setting a new league record with 45 saves in 1984. He finally made a playoff appearance in 1982, throwing 4.1 perfect innings in the NLCS against the Braves over two games, picking up a win and a save. In the World Series, he saved two more games and got a win as the Cardinals beat the Brewers.

After 1984’s record-breaking year, Sutter was finally a free agent. His strikeout numbers had long ago regressed from the more absurd numbers of his first four seasons, but he remained one of the best relievers in the league. Granted, he had an off-year in 1983 and was now on the wrong side of 30. But he was still a top free agent on the market.

For Ted Turner, who never saw a splash he didn't want to make big, that meant an opportunity to bring in a star. In the two seasons since making the NLCS against Sutter's Cardinals in 1982, the Braves had finished second in the NL West in consecutive years. Ever the reactionary, Turner fired Joe Torre and brought in Eddie Haas. As Turner and general manager, John Mullen, decided where to add players, the bullpen didn't appear to be a major priority at first glance. While they didn't have one closer the previous year, the trio of Donnie Moore, Gene Garber, and Steve Bedrosian did account for 38 saves.

Rather, it seemed more like the team needed to add some offense - especially to an infield that mustered 25 homers among the four most-used regulars. None of them had even a .715 OPS.

But Sutter had a pedigree that Turner liked. He offered Sutter nearly $10 million over six years. $4.8 million was paid during the first six years while the other half would be paid to him, with 13% interest, for 30 years after the contract ended. Owners were incensed, censuring Turner for the signing. The censure had no penalty, but it represented a sense that his fellow owners were not very keen on Turner's decision.

Regardless, Sutter joined the Braves for the 1985 season. And everything worked out.

Of course...it didn't. Sutter cruised to open the year, but a tough summer followed. That included a bout of shoulder inflammation which he received a cortisone shot for. By mid-September, the Braves shut him down. After three consecutive good finishes, the Braves lost 96 games and Haas and Mullen lost their jobs.

Sutter opted for surgery that winter, but his numbers only got worse. After sixteen appearances, 18.2 innings, and a 4.34 ERA, Sutter lost his closer job. Soon after, he hit the injured list to open June of '86. He wouldn't appear in another game for the Braves until April 5 of 1988. He blew a save that day, taking a loss. He blew nine saves in total while just saving 14 games. That included a trip to the IL in late July plus opting for surgery on his knee in September.

By March the following spring, we found out what exactly Sutter was dealing with. Unfortunately, his rotator cuff was toast. While he didn't announce his retirement and the Braves opted to keep him on the roster, both sides knew that he likely had thrown his last pitch.

On this day in 1989, the Braves accepted that their big splash signing of 1984 had failed and it was time to move on.

Sutter's final game was against the Padres on September 9, 1988. The Braves had just taken a 5-4 lead in the top of the 11th. Sutter came in and threw ten pitches. A flyout, a groundout, and a strikeout of a future Hall of Famer - then 20-year-old rookie, Roberto Alomar. It was Sutter's 300th and final save. At the time, only Rollie Fingers and Goose Gossage had more. Since he had only played in the NL, he retired as the career saves leader in the NL. Lee Smith, who took his NL single-season record for saves, also eclipsed the NL career mark.

Post-retirement, Sutter waited to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, and, like most relievers, he waited a long time. First eligible for induction in 1994, it wasn't until 2006 that Sutter reached 76.9% of the vote. He was the only player elected that year via the regular vote, but as a sign that the Hall of Fame system has always been kind of broken, only two other players who finished in the Top 10 that year failed to join the Hall of Fame later.

The biggest thing Sutter is known for once his playing career ended was his absurd contract. Bobby Bonilla Day has a cult following, but Bruce Sutter had a similar experience. For 30 years, Sutter received $1.3 million from the Braves. Over the 36 years he received a paycheck from the Braves, he made roughly $44 million. Not too shabby.

His time with the Braves was short-lived and not up to his production levels. He saved five fewer games with the Braves than he had saved in his last year before coming to the Braves. He set career worsts as a Brave after a dominant run of nine years in the majors before coming to Atlanta. Sometimes, big splashy signings just don't work out.

As we head into this offseason, let's hope this version of the Braves can avoid such a fate.

Previous TOTs